Saturday, 11 April 2009

Diamanda Galás

Diamanda Galás (born August 29, 1955) is an American avant-garde performance artist, vocalist, and composer. Galás was born and raised in San Diego, California. She was classically trained in jazz piano from an early age, training which reveals itself consistently throughout all her work. Known for her distinctive, operatic voice, which has a three and a half octave range, Galás has been described as “capable of the most unnerving vocal terror”. Galás often shrieks, howls, and seems to imitate glossolalia in her performances. Her works largely concentrate on the topics of suffering, despair, condemnation, injustice and loss of dignity. Critic Robert Conroy has said that she is ‘unquestionably one of the greatest singers America has ever produced.

She worked with many avant-garde composers including Phillip Glass, Terry Riley, John Zorn, Iannis Xenakis and Vinko Globokar. She made her performance debut at the Festival d’Avignon in France as the lead in Globokar’s opera, Un Jour Comme Une Autre which deals with the death by torture of a Turkish woman. The work was sponsored by Amnesty International. She also contributed her voice to Francis Ford Coppola’s film Dracula (1992) and appeared on the film’s soundtrack.

Her work first garnered widespread attention with the controversial 1991 live recording of the album Plague Mass in the Cathedral of Saint John the Divine in New York.

Sean Lennon

Born October 9, 1975, Sean Taro Ono Lennon is the son of musicians and peace activists John Lennon and Yoko Ono. Kyoko Chan Cox and Julian Lennon are his half-siblings. After Sean’s birth, John became a house husband, doting on his young son until his murder in 1980. Sean was educated at the exclusive private boarding school, Institut Le Rosey (which Prince Edward, Duke of Kent, King Albert II of Belgium, Dodi Al-Fayed as well as Strokes members Julian Casablancas and Albert Hammond, Jr. also attended) in Switzerland, and earlier at New York’s private Ethical Culture Fieldston and Dalton Schools.

His first appearance on record was on Ono’s album Season of Glass (1981), reciting a story that his father used to tell him. At the age of 9, he performed the song “It’s Alright” on the Yoko Ono tribute album Every Man Has A Woman (1984). In 1988 Sean was featured in the cast of Michael Jackson’s Moonwalker. He has recalled working with Jackson as a positive experience. Later in life, his initial efforts as a serious musician came as collaborations: he appeared on Lenny Kravitz’s album Mama Said (1991) and formed backing-band IMA for his mother’s album Rising (1995).

In 1997 Lennon (along with fellow IMA member Timo Ellis) joined New York-based Japanese duo Cibo Matto (Miho Hatori & Yuka Honda) for their second EP, Super Relax. Through his association with Cibo Matto, he was approached by the Beastie Boys’ Adam Yauch, who expressed an interest in his music. Lennon’s debut solo album, Into the Sun, was released in 1998 on the Beastie Boys’ record label, Grand Royal Records. Regarding Grand Royal, Sean has said, “I think I found the only label on the planet who doesn’t care who my parents are and what my name is.

Alvin Lucier

Alvin Lucier (born May 14, 1931) is an American composer of music and sound installations exploring acoustic phenomena, especially resonance, as well as a former member of the Sonic Arts Union along with Robert Ashley, David Behrman, and Gordon Mumma. As a self-acknowledged composer of experimental music, Lucier’s compositions sometimes deal with elements of indeterminacy. Much of his work is heavily informed by science, revolving around the physical properties of sound itself: resonance of spaces, phase interference between closely-tuned pitches, and the transmission of sound through physical media.

Phill Niblock

Phill Niblock (born 2 October 1933, in Anderson, Indiana) is a minimalist composer, filmmaker, videographer, and director of Experimental Intermedia, a foundation for avant-garde music based in New York.

Phill Niblock’s music usually consists of simultaneous drones created from tape (later computer) manipulations of recorded pitches performed by instrumentalists such as Rafael Toral, David First, Lee Ranaldo, and Thurston Moore, on Guitar Too, for Four (G2,44+1x2); and Ulrich Krieger, on Touch Food.

Charlemagne Palestine: Searching for the Golden Sound

Charlemagne Palestine: Searching for the Golden Sound

Interview by Marcus Boon

Palestine at the Beth David Cemetary in Long Island, NY in 1996. Photo by Irene Nordkamp.

I spoke to Charlemagne Palestine by telephone, he in Belgium, in New York in the summer of 2001, after his return from a trip to Iceland. Palestine, as he himself says, met Pandit Pran Nath outside of the circle of musicians and composers associated with La Monte Young and Marian Zazeela, although his work is animated by a similar interest in minimalist strategies for composition and improvisation, and a concern with the transcendental qualities of sound. If you don't know Palestine's work, his interview with Brian Duguid should set you straight. For myself, I've never witnessed any of Palestine's legendary live performances, but I love the CDs of Strumming Music, Schlingen Blangen and Karenina, each of which overflows with euphoric intensity. In conversation, Palestine's voice has an extraordinary musical quality, full of spaces, half finished phrases that convey his meaning musically and poetically, always feeling their way beyond the words.

M: How did you first meet Pran Nath?

CP: It was at the end of the sixties ... I was living on the upper west side of Manhattan in a neighborhood that was known for jazz musicians. A neighbor of mine told me that he'd just heard this incredible singer, and he invited me to go hear him. I'd already sung Jewish sacred music as a child, and was already excited by all kinds of music. So I went, and I heard Pran Nath sing, and he was great. He was looking for students, as where he was staying was only 7 or 8 blocks from where I was living on the upper west side, he was living on 95th Street with two disciples of Baba Ram Dass. So I started to work with him. Immediately it went very easy, since I came from a background of Jewish sacred music, especially his kind of chanting, my voice adapted very well. Within a few weeks, people sometimes mistook me for him. I was a young kid. I mean I was imitating the timbre of his voice, not that I was a great Indian singer. At the beginning, when you learned with him in those days, he tried to help you find the sa. Like the om, the do in Western music. He would do amazing variations on this [sings sa in very PPN way], and then you'd learn the scales. I'd already learnt that in music school ... I'd been searching for a sacred sound in Jewish music so it came very easily to me. I was about 20 years old ...

I studied with him for a few months, and he taught me how to use the tambura, and we'd sing sa and the different notes. He asked me if I wouldn't be his disciple, which meant spending much much time with him. And at my age, it really wasn't what I wanted to do. So at a certain moment I stopped working with him. But for all the following years, because sometimes I had political musical problems with the other generation, Pran Nath always included me in every situation where I was there. He always waved to me - though I never sang to him, and it was clear why, because the idea of giving a commitment and finally the amazing commitment that La Monte, Marian and Terry gave was something I could never imagine giving another person. But this link came because of the sounds themselves and my tradition, I started as a singer, not a keyboard player or composer. I started in music as a singer. And my relationship with synagogue singing. And this put us on a level of very powerful musical communication, which was great. I know he was disappointed, and somewhere, so was I, but even now ... some people say my music is very meditative or centering ... but all the guruisms and gurujiisms ... that kind of giving your life to another culture like India ... though I had many dear friends who were great musicians, and we can even say holy men from India, from Africa ... I loved all that stuff ... But as my culture had disintegrated as a tribal culture, a Jewish New Yorker in the late sixties is not in a Hasidic community, I was already too worldly, too restless to want to return to a foreign culture. But he never excluded me. When there were problems and because I could be a very disruptive person when I felt cornered, he always took my side by including me in the family even though I was the prodigal son who never finally did spend those kinds of years which his technique and his position and Indian music and dance demand. It demands daily commitment. It's not something you can do just like that.

MB: What do you think you learnt from him?

CP: I'd put it more sociologically. There was a great division in my childhood between Oriental or I should say Jewish Oriental sacred music, classical music, jazz, rock ... everything was separated. What he brought by coming to America and by inspiring a bunch of people like Jon Hassell and so on ... all of a sudden you have a whole bunch of guys, I mean La Monte is a Mormon, Terry Riley's an Irish west coaster, I'm a Jewish New Yorker ... at that time we were very conscious of being a very un-tribal culture, meaning that we were all searching for a kind of identity ... all was possible but all our family and tribal units our own born tribal units had disintegrated into an American pablum, and so it was hard to say who you were if you were American. What his being there helped me to feel was that I was continuing the chant of the synagogue, and along with his chant ...we were all part of some larger force that was coming of age, that would then create a kind of world ... even now the audience of young people who listen to my music and get it astounds me ... in those days there were so few people who got it. And people were so fragmented ... you were either in this kind of world or that kind of world ... so his being there and attracting so many people and his coming from such an ancient culture ... was a very powerful social force, bringing this ancient tribal tradition, which musicians like us had lost touch with, certainly white musicians.

MB: What about this tradition was important that it should manifest in the west?

CP: Ooof. It even happened with Merce Cunningham or John Cage .... at a certain moment, we were given all the freedom to do what we want. I went to conservatory, and there were people I met, and even now there are people who spend their lives from the time they're 7, 12 hours a day developing a musical tradition - piano, voice ... it's a paternal or maternalistic system ... ballerinas for instance ... so it's not like you wake up in the morning and you're the king of your own world and you invent your own music. It's something that came out of the western [classical?] idea ... but at a certain moment you wake up in the morning and you say: well what the hell do I want to do?? That system that came from an ancient place where there's already this hierarchy where you don't have to think about what to do for years and years, maybe for 30 years you won't have to think about what to do because there's someone above you who will show you, who will mold you, who will inspire and guide you. And that aspect of guruisms that I used to criticize I understand because there were many very interesting and intelligent people who felt that need. That was one of the things that drugs tried to ... that's why someone like Richard Alpert becomes Baba Ram Dass ... he too was looking for another force bigger than himself to show him some great magic in the world that he could no longer do by himself. That's maybe what psychedelia was about. That you took some kind of another force, whether it was a human being or a drug which ... you were no longer the top of your heap ... you were more like a leaf in the wind where somebody else took care of the power structure. And that I think was somehow very important in those times. Especially ... for a lot of white people ... although I'm Jewish I lived in a white society ... but because I was born in a culture that's not exactly white through and through, so I had this ancient link ... maybe you have this still in Ireland ... but in America we've lost that. Maybe in the UK you still go to a place and ancientness is still there. In Iceland, they arrived in 900 AD, but when I watch them and see what they do ... 900 is not such a long time ago. That comes out of the simplicity of a tribal culture. Iceland is a modern culture, but it's a very tribal culture.

MB: And it's to do with discipline ... discipline produces a kind of authentic experience?

CP: ... And it lets you know that carrying on a tradition is OK. That you don't have to be an iconoclast every day, you don't have to destroy what was there yesterday. I was brought up with that notion of genius: that you do something that nobody else did and you try not even to do what you did after awhile otherwise you're already finished. Which is the contrary of the oriental tradition where you make more and more perfect the tradition which goes from generation to generation ... and certainly he was the incarnation in this time of a very ancient tradition. So he was him, but he was also an entire culture.

MB: Are there particular works of yours, where you do see the resonance of your studies with Pran Nath?

CP: Well, Karenina is an easy one. That came out just after his death. Schlingen-Blangen is a kind of sa piece. It's not sung, it's sung by an enormous instrument, but it's a way of humming in space ... but in a funny way my teacher Sebastian Engelberg, Austrian Jew in the opera tradition, died quite a few years before, that's why he became my teacher ... he was looking for the golden sound. The whole concept for me of the golden sound was the sa of Pandit Pran Nath.

Performing Karenina at the J & J Donguy Gallery, Paris in 1997.

MB: The sound that contains all the possibilities of sound?

CP: Yeah - and the search for this perfect sound. And the pure voice without anything else is the most intimate and expressive sound that a being can make. If its an animal, their screech ... the bark of a dog ... for me there's nothing more intimate, and the essence of the animal or the being is the voice. Even though I did many things that were not the voice. But I started with the voice. And he was the voice.

MB: But even your non-vocal drone pieces ...

CP: Yeah I see them as taking that ideal and putting it in another context. In my sense I don't know what that perfection is. Finally I do it in a very sort of Jewish way ... searching, neurotic, schizophrenic, frenetic, sometimes calm sometimes chaotic, searching for this perfection ... a way that's kind of Kabballic ... something unattainable ... it's not like a beautiful smiling Buddha on a mountaintop somewhere. Meaning, for somebody for me.

MB: It's more of a struggle ...

CP: Exactly. And he was a struggling man. He loved his whisky ...

MB: I heard he had a taste for Chivas Regal ...

CP: As did my father. As do I! (laughs) Sometimes to very cataclysmic extremes. On that level I also touched with him. Though we didn't discuss it.

MB: Did you have a sense of what the struggle was about?

CP: A sense of what the struggle was about ... well ... life is a struggle! Certainly when you're in a tradition like that, with a continuity, with that as a center, a pole to secure yourself from the winds that can throw you from side to side ... and the creative process ... someone like him was not just a good virtuoso singer ... because also in India you find people like the Dagar Brothers who are fantastic virtuosos. And maybe also because he also was out of his culture too he rarely went home, he preferred to be in the west. As we were tormented by being a lost culture looking for our roots, he was tormented, being from a culture with enormous roots that he could no longer socially live in as a normal member of. He had a lot of ghosts and angst that in traditional Indian society were not looked well upon. But he wasn't the only one ... I met others ... and you see it with jazz musicians too ... they gave all their lives to their music, and their personal lives were less ecstatic than the sounds they made and they suffered from all these questions and problems dealing with that, as many artists do.

MB: Right. You see it in a lot of the spiritual teachers who came from wherever they came to the west in the sixties and seventies too. Moving to the west and taking on that sort of rootlessness was something very painful.

CP: It makes me think ... the difference between drinking in a culture and drinking like that is that you're alone. In Greece, even in French families, there are thirty of you and you're drinking for a festale, a marriage. You're all together - it's not lonely. But then you come to another culture, and it becomes a lonely kind of task, and that creates another kind of alcohol.

MB: It's said that Jewish people are less susceptible to alcoholism because they tend to be raised in families where alcohol is used in a social context, and it's much more integrated into their lives.

CP: In my family that was the epoch when my father drank with his brothers and cousins and his Chivas Regal was a social drink. I drank with him at the table for shabas, we drank together. But when I came of age, that community no longer existed. My cousins had moved, they had become Americans and there was no longer this community. But the alcohol stayed! (laughs) It's funny, you called me at the hour when I have my aperitif - I'm drinking my Johnny Walker. My wife knows it's like a sacred hour of the day for me. When I start my first whisky. I used to drink sometimes at any time of day. Now, after six ... so if there's anything I need to do that needs a certain precision or objectivity ... but then I try to drink pleasantly, to enjoy it ... and in these years I've come to enjoy alcohol.

MB: Were there specific pieces of advice that he gave you?

CP: No. We never spoke like that. It was always in the sound. He always had me sing. He just looked in my eyes ... for me he came from a tradition in sound that was the closest to anything that I could have imagined ... I sang with some of the great singers in Jewish tradition, they're the equivalent of Pran Nath for the Jewish faith. They're not rabbis, though they can also be rabbis ... they studied, they learned the books and became learned men, but they were the men that sang to God, and for the people in all the traditional rituals. And I studied with several of them - with them, because often a young boy would do duets with them, never a girl ... and even with them our relationship was totally sound. So we did very little talking except to say, you're out of tune duh duh duh ... and it was through the sound that we communicated ... and with him also that was true. I sang so easily his style. That's why people thought I sounded like him, because I could imitate the sound. Not him of course, but the sound. The sound was easy for me.

Palestine at his bar mitzvah, New York City, 1960.

MB: Were there works where you were formally concerned with raga like structures?

CP: No. I've never been good at ... in western music, in eastern music, I've always been kind of a poetic deadhead ... I've never been good at the mathematics. I could just sort of get it! I was in the conservatory for five years to keep out of the Vietnam war ... I learned certain techniques, but I never used them. They were just something I learned because they exist. Interesting to analyze. But I always learned everything by ear. I loved the sound of those words. Like in Karenina I invent ragas and words that could mean something ... I always have the dream that some day someone will listen to them and know exactly what they mean because it's their language. Like when I was in Iceland, they have such a special language and everyone understands because they speak the language, but when you're a foreigner, it just sounds like you're muttering and sputtering all these strange sounds and that I love! (laughs) That's the level I love, that mysterious sputtering and juttering in a language. That's what it was like for me to sing with him. Like re ne na ... (sings)

MB: You have that solemn quality in your voice that he has ...

CP: I had it in five minutes. As soon as I met him, he looked at me with those eyes, those sad eyes and his teeth, one tooth a little bit off, when he opened his mouth it wasn't perfectly symmetrical, it was a little bit off and I knew exactly how he felt because that's how we sing in Hebrew singing ... you cry and you do these lamentations. It just was so easy. It touched something very ancient. About the man ... on the planet ... blah blah blah!

MB: When you were working with different ethnic musics, did you come to feel that there were particular ways of doing it or ways to avoid or did you just go on your nerve?

CP: Sometimes I feel like I've been too floating ... a whirlpool of wind and water ... but I've never been able to decide those kind of questions. They seem to me something very untouchable. Some deep part of me feels they shouldn't be touched. And then there are other people who actually do set up these systems and they work. Even for ballet, they're magic when they work, yet they come from a lot of repression and discipline and ego battling. But I've never been able to ... so I've always kept outside. And that's what keeps me the prodigal son. Even in this story, I'm on the outside. I use what I use and I do what I do. I'm sort of an uncle, I'm not a father. I'm just my own asshole ... going through my day. I try to be the best possible asshole I can be!

Singing in 1972, San Francisco. Photo by Elaine Hartnett.

Searching for the Golden Thread:

an interview with Charlemagne Palestine

My Cocaine Museum

My Cocaine Museum

Michael Taussig

chapter 2

my cocaine museum

I ask a friend upriver in Santa María what happens to the gold he mines and sells. He says it goes to the Banco de la República in Bogotá, which sells it to other countries. "What happens to it then?" "I really don't know. They put it in museums…" His speech fades. Lilia shrugs. It's for jewelry, she thinks. And for money. People sell it for money. It goes to the Banco de la República and they get money for it…In a burst of self-righteousness, I ask myself how come the world-famous Gold Museum of the Banco de la República in Bogotá has nothing about African slavery or about the lives of these gold miners whose ancestors were bought as slaves to mine the gold that was for centuries the basis of the colony—just as cocaine is today? So what would a Cocaine Museum look like? It is so tempting, so almost within grasp, this project whose time has come…

Within grasp?

Project?

Where better, then, to start than with the twelve-inch-long bright red wrench, lovingly displayed on our TV screens in New York City last week, as described to me by my teenage son, an inveterate watcher of TV? Is not this oversize wrench the most wonderful icon for My Cocaine Museum? I mean, where better to start than with the mundane world of tools, antithesis of all that is exorbitant and wild about cocaine, and yet have this particular tool, which, being so fake and being so grand, so far exceeds the world of usefulness that it actually hooks up with the razzle-dazzle of the drug world? How these two worlds of utility and luxury cooperate, to form deceptive amalgams that only people privy to the secret can prize apart, is a good part of our story and therefore of our museum too.

For according to U.S. federal prosecutors, gold dealers on Forty-seventh Street in Manhattan are paid by cocaine smugglers to have their jewelers melt gold into screws, belt buckles, wrenches, and other hardware, which are exported to Colombia, from where the cocaine came in the first place. U.S. attorney in Manhattan James B. Comey points to "the vicious cycle of drugs to money to gold back to money."

Could we not have predicted this, given what we already know about the tight connections in prehistory between gold and cocaine? The exotic and erotic gold poporos in the Gold Museum have long unified the world of gold with the world of coca. Used to contain lime from crushed seashells and burnt bones so as to speed up the breakdown of the coca leaf into cocaine, the poporo unifies the practical world with the star-bursting world of cocaine and cannot be too far removed from the beauty of the oversize red wrench, at once so practical and impractical. "On 47th Street, everything is on trust," says a jeweler, making it all the easier, it appears, for an undercover agent from the El Dorado Task Force who came saying he wanted to smuggle gold into Colombia and needed to change its shape. The jeweler replied to UC (which is how the undercover agent is now referred to) that he would provide gold in any shape UC wanted.

Any shape UC wanted.

How perfect is gold, the great shape-changer, the liquid metal, the formless form. How perfect for our Cocaine Museum to have such hefty metaphysical kinship with a substance that, like the language of the poet, can be twisted and tuned to the music of the spheres. I can think of only one other substance that rivals gold and cocaine in this regard and that is cement, once known as liquid stone, which now covers America.

Where better to start, then, than in the canyons of Gotham, with Wall Street brokers buying their drugs from a Dominican man in a nice suit in the men's room sniffing cocaine. At the same time across the East River at Kennedy Airport, there is a Chesapeake Bay retriever, also sniffing, urged on by its U.S. Customs-uniformed mistress, "Go, boy! Go find it! Good boy!" as small-statured Colombians draw back in horror at the baggage carousel when their clear plastic-wrapped oversize suitcases come lumbering into sight and smell—plastic-wrapped in Colombia by special businesses that come to your home the day before the flight to seal your baggage against a little slippage.

A real American decides enuf is enuf. The dog has gotten out of control, he decides, and he tells its handler to back off as the dog jumps up and down slobbering on his chest. "You have your constitutional rights," says the handler. "Here everyone is guilty until smelt innocent," and she urges the dog to leap higher. You need a large dog for this sort of work. The small ones may be smarter but get trampled on. Whoa! Watch out! Dogs and their happy masters and mistresses come running helter-skelter down the aisle as if out in the park for a romp. They must be thinking of the dogs leaping for red meat under the wings of the planes out on the tarmac far away at Bogotá. Lucky Third World dogs. When the animal is at play, the prehistoric is most likely to be snagged.

Sometimes they find a frightened Colombian they suspect of having swallowed cocaine-filled condoms before the flight. They force-purge the suspect. I mean, how many days do you think the DEA's gonna wait on some constipated mule? In the toilet bowl swim tightly knotted condoms like pairs of frightened eyes, blown up Salvador Dalí-like streaming out of the bowl, across the floor, and along the ceiling, showing the whites of terror as other condoms explode in the soggy blackness within the stomachs of couriers.

Far from the surefooted world of dogs, yet no less dependent on instinct because they cannot distinguish coca from many other plants, are the satellite images used to prove the success of the War Against Drugs, spraying defoliants onto peasants' food crops as well as onto coca, forcing the coca deeper into the forest and now over the mountains and into the Pacific Coast. The U.S. ambassador to Colombia has been quoted as saying, "It's quite possible we've underestimated the coca in Colombia. Everywhere we look there is more coca than we expected." Remember the "body counts" in Nam?

The noose is tightening, says the priest. Along with the cocaine come the guerrilla, and behind the guerrilla come the paramilitaries in a war without mercy for control of the coca fields and therefore of what little is left of the staggeringly incompetent Colombian state. You edge into a dark room with sounds of a creature in distress illuminated by a red glow casting shadows of vultures on the wall of the slaughterhouse early morning as amidst the smell of warm manure, the lowing of cattle, and thuds of the ax, poor country people line up closer together shivering to drink the hot blood for their health as the president of the United States of America signs the Waiver of Human Rights in the Rose Garden that releases one billion dollars' worth of helicopters fluttering out of the darkness like the bats the Indians made of gold, the caption to which tells us that being between categories—neither mice nor birds—bats signified malignity in the form of sorcery, and compares the helicopters with the horses of the conquistadores breathing fire and lightning on terrified Indians.

But the Indians were always good with poisons and mind-bending drugs such that high-tech solutions turn out to be not all that effective in the jungle, so don't despair: there's every chance the war and the massive economy it sustains will keep roaring along for many years yet. Speaking of Indians, here's a familiar figure to greet you, that huge photo you see in the airport as you walk to immigration of a stoic Indian lady seated on the ground in the marketplace with limestone and coca leaves for sale and in front of her, of all things, William Burroughs's refrigerator from Lawrence, Kansas, with a sign on its door, Just Say No, as an Indian teenager saunters past with a Nike sign on his chest saying Just Do It and a smiling Nancy Reagan floats overhead like the Cheshire cat gazing thoughtfully at an automobile with the trunk open and two corpses stuffed inside it with their hands tied behind their backs and neat bullet holes, one each through the right temple and one each through the crown of the head. El tiro de gracias. Professional job, exclaim the mourners crowding around the open coffin and holding the neatly dressed children high for a better view. "I know when I die," I say to Raúl, "I want it to be here in this pueblo with these people around me." He looks at me oddly. I have scared him.

One of the bodies is Henry Chantre, who while doing his military service in the Colombian army used to pick up and transport drugs into Cali for his officers—so they say—and when discharged got into trafficking himself, a shiny SUV, a blond wife, handsome little children, and one day a deal went sour and he was found stuffed in the trunk of an abandoned car by the bridge across the Río Cauca. A long way from Manhattan's East River. In one sense. Strange, these rivers, so elemental, first thing the conqueror does is find a river snaking its way into the heart of darkness and all of that, for trade, really, canoes, rafts, that sort of thing, rail and road an afterthought decades or centuries later, water spanning the globe, the bridge spanning the river connecting Cali to this little town south, where Henry Chantre lies staring at you, the town milling round, the bridge being where most of the bodies end up getting dumped, heaven knows why; what weird law of nature is this, the river, the bridge, why always the same spot, macabre compulsion to dump bodies in the burnt-out cars and gutters there in the no-man's-land by the bridge between categories, like the bats, neither bird nor mouse, sanctified soil teeming with chaos and contradiction here by the river where black men dive to excavate sand for the drug-driven construction industry in Cali. Father Bartolomé de las Casas, sixteenth-century savior of Indians in the New World, wrote passionately about the cruelty in making Indians dive for pearls off the island of Margarita in the Caribbean. Nowadays, long after African slavery has been abolished, the slavery that replaced the slavery of Indians, it's considered routine to dive for sand, not pearls, the strong ponies so obedient braced against the current, carrying wooden buckets.

We need figures, human figures, as strong as these squat ponies braced against the current, and in the early morning mist by the river comes in single file the guerrilla, who, except for their cheap rubber boots and machetes, look the same as the Colombian army, which looks exactly the same as the U.S. Army and all armies from here to eternity most especially the paramilitaries, who do the real fighting, slitting the throats of peasants and schoolteachers alleged to collaborate with the guerrilla, hanging others on meat hooks in the slaughterhouse for days before executing them, not to mention what they do to live bodies with the peasants' own chain saws, leaving the evidence hanging by the side of the road for all to see, and worst of all, me telling you about it. Hence the restraint in the display case in our Cocaine Museum with nothing more than a back ski mask, an orange Stihl chain saw, and a laptop computer, its screen glowing in the shadows. When they arrive at an isolated village, the paras are known to pull out a computer and read from it a list of names of people they are going to execute, names supplied by the Colombian army, which, of course, has no earthly connection with the paramilitaries. Just digital. "It was a terrible thing," said a young peasant in July 2000, in the hills above Tuluá, "to see how death was there in that apparatus."

The paras are frank even if they like to be photographed wearing black ski masks despite their being hot and prickly. As of July 2000, some 70 percent of the paras' income, so they as well as the experts say, comes from the coca and marijuana cultivated in areas under their control in the north of the county, drugs that will make their way stateside. Yet up till that date, at least, the paras get off scot-free. Their coca was rarely subject to eradication, and the government's armed forces had never, ever confronted the paramilitaries. Instead the thrust of the U.S.-enforced war was to attack the south where the guerrilla are strongest and leave the north free. The War Against Drugs is actually funded by cocaine and is not against drugs at all. It is a War for Drugs.

Our guide motions to the ripples spreading over the river where corpses are daily dumped, and men dive for sand for the remnants of what was once a thriving industry, building the city of Cali, rising rainbow-hued through layers of equatorial sunbeams thickened by exhaust fumes. Transformed by drug money invested in high-rise construction and automobiles, the city now wallows in decay, with many of its apartment towers and restaurants empty. Nothing like cocaine to speed up the business cycle.

To the south of the city, in the next room of our Cocaine Museum, are the remains of peasant plots like bomb craters filled with water lilies in the good flat land from which the earth has been scooped out eight or more feet deep so as to make bricks and roof tiles for when the building boom in the city was in full swing. This rich black soil was once the ashes of the volcanoes that floated down onto the lake that was this valley in prehistoric times. Peasants sold it, their birthright, taking advantage of the high prices for raw dirt and because agribusiness created ecological mayhem with their traditional crops. Then the boom stopped and now there is no work at all. There is no farm anymore. Just a water hole with lilies that the kids love to swim in.

And to tell the truth, for a lot of people even if there was "work" in the city, nobody would want it. Dragging your arse around from one humiliating and massively underpaid job to another—less money, really, than the women get panning gold on the Timbiquí (Can you believe it!). That's all over now, the idea of work work. Only a desperate mother or a small child would still believe there was something to be gained by selling fried fish or iced soya drinks by the roadside, accumulating the pennies. But for the young men now there's more to life, and who really believes he'll make it past twenty-five years of age? If they don't kill each other, then there's the limpieza, when the invisible killers come in their pickups and on their motorbikes. At fourteen these kids get their first gun. Motorbikes. Automatic weapons. Nikes. Maybe some grenades as well. That's the dream. Except that for some reason it's harder and harder to get ahold of, and drug dreams stagnate in the swamps in the lowest part of the city like Aguablanca, where all drains drain and the reeds grow tall through the bellies of stinking rats and toads. Aguablanca. White Water. The gangs multiply and the door is shoved in by the tough guys with their crowbar to steal the TV as well as the sneakers off the feet of the sleeping child; the bazuco makes you feel so good, your skin ripples, and you feel like floating while the police who otherwise never show and the local death squads hunt down and kill addicts, transvestites, and gays—the desechables, or "throwaways"—whose bodies are found twisted front to back as when thrown off the back of pickups in the sugarcane fields owned by but twenty-two families, fields that roll like the ocean from one side of the valley to the other as the tide sucks you in with authentic Indian flute music and the moonlit howls of cocaine-sniffing dogs welcome you to the Gold Museum of the Banco de la República.

Something like that.

My Cocaine Museum.

A revelación.

Copyright notice: Excerpt from pages 13-20 of My Cocaine Museum by Michael Taussig, published by the University of Chicago Press. ©2004 by the University of Chicago. All rights reserved. This text may be used and shared in accordance with the fair-use provisions of U.S. copyright law, and it may be archived and redistributed in electronic form, provided that this entire notice, including copyright information, is carried and provided that the University of Chicago Press is notified and no fee is charged for access. Archiving, redistribution, or republication of this text on other terms, in any medium, requires the consent of the University of Chicago Press.Peter Wyngarde

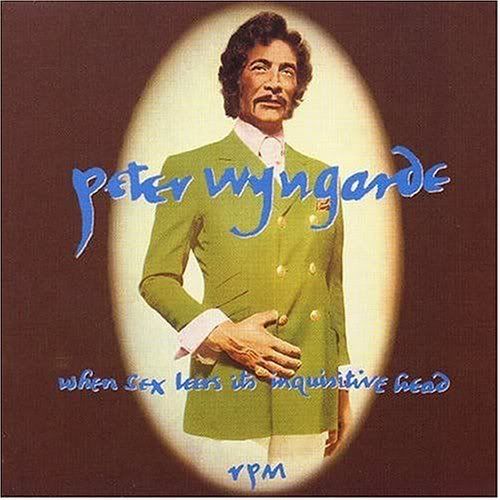

Salut, I am Peter Wyngarde...welcome. Why don’t you make yourselves comfortable. Kick off your shoes, relax and let the soothing sound of my voice lead you into a frenzy of psychedelic vintage suits and ties. Many of you will remember me most as the lovable debonair playboy ’Jason King’ in my own long running series of the same name, others from the big screen in Night of the Eagle or more recently Flash Gordon. Those attending the theatre in the 60’s and 70’s are sure to have caught me in the flesh at one point or another. Today I address you under a different guise. Many years ago a little bit of musical magic was made with myself at the helm of a masterpiece. My first and only album titled simply ’Peter Wyngarde’ was withdrawn from shelves within a week of being released in 1970, due to, I can only imagine, the deep seeded myth and conspiracy within the enchanting lyrics. Do not worry friends, it was released years later under the more flamboyant heading ’When Sex Leers it’s Inquisitive Head’, as the enormity of my presence was realised through television. I now sit night after night by my rich pine writing table, penning what is sure to be the album of the century. Keep me close to your hearts. I remain as always your eternal servant....’Peter.’

www.myspace.com/peterwyngarde

Lau Nau

Lau Nau’s abstract folk is a mosaic of a myriad of instruments that fall where they may, with free open structures, balancing on a thin wire of logical evolution, with surprising harmonies. Still, the songs have strong backbones. Melody is suggested through the contours of a wandering and warm voice. Lau Nau’s debut album is released by the Chicago-based label Locust and is an amazing slice of outdoor sounds, multi-instrumentation, surreal and lush vocals. "The music, compared to reading literature, is a book with the leaves spread in the order of a tree. You get a three-dimensional picture, like nature’s sounds from a human soul."

Monday, 6 April 2009

Sunday, 5 April 2009

El Topo Soundtrack

![El Topo front cover [front cover of El Topo soundtrack]](http://www.dinosaurgardens.com/wp-content/uploads/2006/06/ElTopoFront.jpg)

Following up on the previous Holy Mountain soundtrack post by Brakhage, I humbly present the entire Douglas 6 reissued vinyl soundtrack to Alexandro Jodorowsky’s motion picture, El Topo (aka The Mole), often referred to as “the first midnight movie”. Based on brief online searching, it appears neither the original Apple label release nor the Douglas 6 release are on CD yet but supposedly, according to this trailer there will finally be an official (hopefully North American NTSC) release of El Topo on DVD as well as Holy Mountain and Fando and Lis, so it would logically follow that the soundtracks for both could be released on CD. One can hope anyway. Here are the liner notes transcribed:

MUSIC OF EL TOPO

Composed by Alexandro Jodorowsky

SHADES OF JOY

Arranged and conducted by Martin Fierro

EL TOPO blew my mind like it’s blown everyone else’s. But being Mexican I felt especially close to it, felt a very complete connection with it. So I think there’s a real organic relationship between what we’ve done with the music on our record and what the music is essentially about. The music, like the rest of the film, is very spiritual – Alexandro’s a very far out cat. What we’ve done with the music sort of takes up where Alexandro left off. In terms of styles and forms we take in many things that have been happening in music since the soundtrack was made, and that makes the music on the record more related to what’s happening on the street and in the society now.

The cats in Shades Of Joy, they’re all ‘bad’ cats, with different backgrounds and experiences. And we can play a lot of different trips, from Rock to Jazz to Latin to Hillbilly to Country and Western. We got everything into the music – all the things we’re able to do. You see, all the tunes in EL TOPO portray a mood and have so many emotions to explore and develop. There is frustration and pain and love in them. There are pensive moments and happy moments. I took the songs and shaped them the way I saw fit. I think we succeeded in complementing Alexandro very well.

Martin Fierro

I believe that the only end of all human activity – whether it be politics, art, science, etc. – is to find enlightenment, to reach enlightenment. I ask of a film what most North Americans as of psychedelic drugs. The difference being that when one creates a psychedelic film, he need not create a film that shows the visions of a person who has taken a pill; rather, he needs to manufacture the pill

I think there are multiple influences in El Topo – I have them all: the influence of all the books I’ve read and all the films I’ve seen, of all the winds that have blown against my skin, of all the stars that have exploded during my lifetime, of each manifestation of the now manifested, of each flea that’s shit on me. Especially a flea I met in 1955. It shit on me in such an incredible way, that it changed my life. I’m sure that flea’s in my film

Alexandro Jodorowsky

ON LISTENING TO MARTIN FIERRO’S MUSIC FOR EL TOPO

I was a seed

Watching itself grow on a tree

Knowing

I was the tree,

But feeling

Apart from it.Earth and water

Came together

With my energy

And the fruits and branches

Were larger far beyond

What I had ever thought.I sat there

Watching myself grow.I wanted to leap up out of

The depths of the earth

And drop into the heart of the fruit

Be the future seed, one of them,

Not be the origin.Alexandro Jodorowsky

Side 1

Side 2

Produced by: Alan Douglas – Doris Dynamite

Eddie Adams, Ken Balzell, Hadley Caliman, Jack Dorsey, Martin Fierro, Luis Gasca, Jackie King, Jerry Love, Mel Martin, Frank Morin, Ivory Smylie, Roger ‘Jellyroll’ Troy, Howard Wales, Peter Walsh, Jymm Young

All selections composed by Alexandro Jodorowsky except Freakout #1,

By Martin Fierro, published by Editions Douglas Music / BMI.

Label: Douglas 6

Via Dinosaur Gardens

![Martin Fierro [photo of Martin Fierro]](http://www.dinosaurgardens.com/wp-content/uploads/2006/06/ElTopoMartinFierro.jpg)

![Jodorowsky [photo of Alexandro Jodorowsky]](http://www.dinosaurgardens.com/wp-content/uploads/2006/06/ElTopoJodorowsky.jpg)

![El Topo back cover [back cover of El Topo soundtrack]](http://www.dinosaurgardens.com/wp-content/uploads/2006/06/ElTopoBack.jpg)